17 Sep The Six-Step Mission Planning Process

Flex planning starts with what the team leader intends the mission to achieve—the why—and finishes with the team’s clearer mission objective and the course of action to get there. Together, the ‘leader’s intent’ and the course of action will answer the who, what, when . . . and why and what-if. Whilst there are different variations out there, our experience suggests the following steps will get you where you need to go!

- Set a mission objective, that meets the leader’s intent and is clear, measurable, and achievable. (Where do we need to be, and why?)

- Identify any threats, controllable and not. (What’s in the way?)

- Identify the resources you can draw on. (What can help us to our objective, or deal with what’s in the way?)

- Identify the lessons learned from previous debriefs that you can draw on. (What did and didn’t work before)

- Set out a course of action (Who does what and when to reach the objective?)

- Set your contingency plans, the what-ifs. Prepare for the worst. (What do we have in place for the unexpected?)

The Leader’s Intent

No matter how clearly defined your achievable objective is, there has to be a point to it! That point is to get your team and your organization one step closer to your ultimate destination. That gives the mission purpose, and that purpose motivates your team. It’s up to the team leader to make that purpose clear. The mission planning will set a specific, immediate objective, but the leader’s intent is the intended effect of that mission.

All of this is about aligning your team’s mission towards your high-definition vision of your destination (HD Destination). Each mission is planned to pursue a strategy or campaign towards the HD Destination. It may go exactly as planned, it may go a little off course, or it may be opportunistic—but every mission is pointing in the right direction! Without that clear alignment, good people are on good missions that may seem worthwhile but don’t advance the team or the organization towards its goals.

Step 1: Set the Mission Objective

People really like to know what they are trying to do, and why that’s worth doing. That’s why they’ve joined your team, your club, your business, your government. So if a good mission objective is given to them, you’re off to a good start! But a Flex mission objective is one that people create themselves, and that takes their motivation to a whole new level.

This is true of both short-term and long-term missions. A short-term mission has the advantage of being something that you and I can go out and start executing today. If you don’t have clarity around that, it will be a long day out. But a poor objective for a long-term mission, even an organizational strategy can waste years, resources, careers! Don’t do that. A Flex mission objective will be clear, measurable, achievable, and aligned.

Clear

Mission objectives should be CLEAR. That means that everyone briefed to do the job knows exactly what the objective is. The mission objective is a sentence, and you have to test two things about a sentence: the words and the order you put them in. Push hard on the meaning of every word. If it’s an acronym, does your team know what it stands for? or if it’s a generic business term (sales, competition, costs), have you given a precise definition? It is guaranteed that if there’s any shadow of a doubt, someone on your team will interpret the word the wrong way. Someone will get hurt. Don’t give them that chance!

Measurable

If you get the words and structure right, your objective will be clear and unambiguous. That idea slides into it being measurable. Immediately after the mission, you’ll be asking ‘Did we achieve our objective?’ There are only two answers that matter—‘yes’ or ‘no’. Everyone must be able to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’—as soon as the mission is complete. Anything else means your planning didn’t frame a clear and measurable objective.

To be able to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’, means you’ve got a specific action or number and time in the objective that can be measured objectively. If there’s a number involved, you need to be able to chart it. If there’s a checklist involved, you need to be able to tick it off. In the same vein, a mission objective must be to do something tangible. Quality and collaboration can be measured, but only if you set out clearly what that measure will be

Finally, a measure is an objective measure, not an opinion. Don’t ask your team to go out there and bust a gut when the objective is ‘to hold the event to Pete’s satisfaction’. Would that be Pete in a good mood or a bad mood? At the event or elsewhere? Conscious or unconscious? Objectives and opinions don’t mix. It’s a lot more productive to get rid of the opinions.

Achievable

Mission objectives have to be achievable! Nothing erodes motivation and energy faster than being asked to do the impossible. Tough missions can be great challenges that bind a team forever. A mission can be a stretch, it can ask for a brutal effort. But it has to be possible.

For the modern army and air force, the loss of one life means that a mission has failed. Leaders who ask for another’s inevitable sacrifice—where an option exists—immediately lose their respect. Business is not life and death, but the concepts of sacrifice and respect are real enough. A team or an individual that’s on a road to nowhere will not travel it far.

Fortunately, the Flex planning process will determine whether an objective is achievable or not, and the team itself is leading that process. If it looks impossible, there are options! The team may seek additional resources. More often, the objective can be adjusted. The best adjustment is to shorten the reach of the mission. If the original mission looks impossible yet still valuable, break it down into steps and make the first one achievable. Then see what’s possible from there.

Step 2: Identify Mission Threats

As a fighter pilot, someone was out there wanting to shoot us down. We wanted to know everything, but nothing, about who those people were and what their jets could do. You get very serious about gathering information when your life is on the line.

The threats may not be as deadly in business, but they are just as real and just as threatening to your career and company. ‘Be paranoid!’ Intel’s first CEO Andy Grove used to say. Paranoid in the most constructive of ways. Dig down and really work out what your weaknesses are, what could go wrong, what could go so right that it would distract you from your actual objective, and also what your competition could do. There will be threats, no matter how seemingly straightforward a mission is.

At this stage of planning, your team needs to identify what your threats are—internal and external—and whether you can control them. Like everything in Flex and life, you’re aiming at a sweet spot: not too few threats that you miss some, not too many that they become demoralizing and your plan to meet them becomes chaotic. It’s here too that it’s worth making an effort to classify your threats. This helps your team to discuss those threats, to work out how important they are, to work out what to do with them. If a threat is controllable you can plan for that control in your course of action. If it’s not, you’ll need a contingency plan.

Internal threats

‘We have met the enemy, and he is us.’ Said Walt Kelly to introduce his Pogo cartoon in 1953, as with so many cartoonists so dangerously close to home truths. It’s a great line because it points you one way, then brings you back to the place that matters.1

We might try to deny it, but our personal, internal threats are the most common, and we get distracted; we lose confidence, focus, energy, or the will to lead. These are ever-present threats that we deal with in the execution phase of the Flex cycle. The internal threats that we’re most interested in here are those, relevant to the mission, which exist within your team or the organization itself.

The biggest internal threat we see across all our clients? We call it CIA. These are the deadly triad of complacency, indifference, and apathy. They can appear anywhere: in you, in your team, your customers, your boss. People who just possibly don’t care about your mission anywhere as much as you need them to. With CIA, your team is not really going to consider its threats. You’ve assumed them away. Nothing to worry about here. And so have the rest of your organization: they’ve got their own issues to deal with, so don’t expect them to save you from yourself. Back to Andy Grove—be paranoid. Use Flex and you won’t have to deal with CIA.

External threats

Again, you need to be as curious and imaginative as possible to identify threats to your mission that come from outside your organization. They will depend on the nature of your mission and its timeframe. Make up a checklist of the world of possible threats—weather, logistics, audience, content—and run through it as a habit! For more significant business missions, the external threats are larger but are unlikely to emerge without warning. For these, you may well need a framework to act as your team’s checklist.

Think also of the triple bottom line of profit, people, and the planet. What is happening in your market: your competitors; economic, regulatory, and technology trends? What social and environmental shifts are occurring that may change assumptions about the resources you have available? Are people more comfortable with online transactions, even with strangers in peer-to-peer models, making old brands more susceptible? Will your customers still be happy to pay you in cash, when they really like paying online and tracking their expenses through apps?

Keep building your knowledge on trends that will affect your business, in any respect. Any one of them might decide to announce itself on your mission. Keep building up your potential responses. Use each mission planning episode as an opportunity to quickly check in on those trends. It’s standard risk analysis.

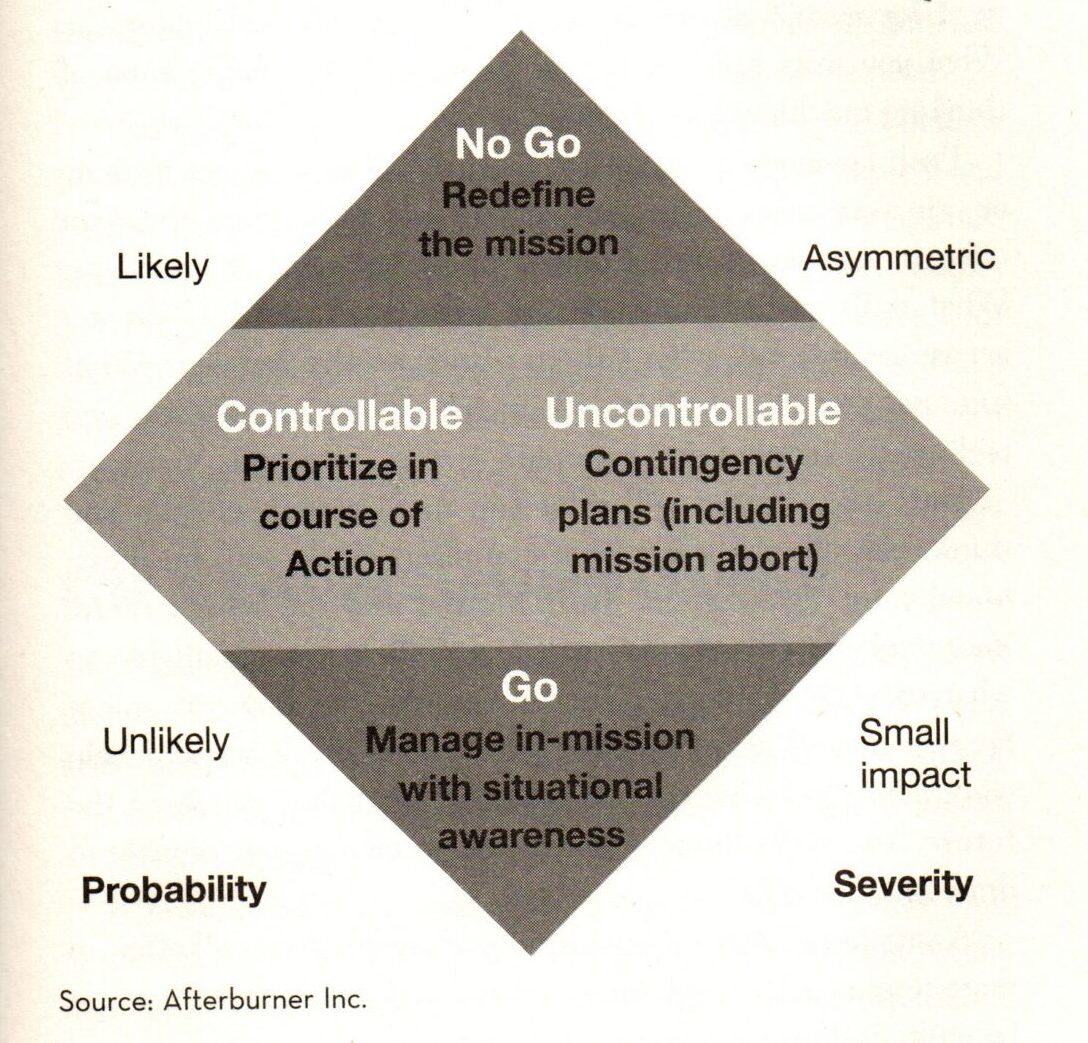

Controllable or uncontrollable threats

Controllable means that the planning team can negate, mitigate, or avoid the threat. That is, the team can take some action so that the threat does not take place (negate it) or if it does, it will not affect the mission because its impact is reduced (mitigated), or the mission is planned so that it doesn’t matter if the threat is realized or not (avoided). If the team can control a material threat, it should do so in its course of action—the plan includes an action to control the threat (Step 4). If the team can’t control the threat, it becomes a contingency (Step 6)—the plan will change if the event occurs.

It’s not always easy to distinguish between controllable and uncontrollable threats. Let’s take the perennially safe ground of the weather. You’ve got an outdoor event coming up, and it may rain. You can control that threat—either by mitigating it (umbrellas and sturdy marquees) or avoiding it (holding it indoors). But a thunderstorm? If you’ve gone ahead with the outdoor event, a crashing storm is pretty much uncontrollable. You’ll need a contingency plan, and a time to decide whether to put that plan into action.

Threat triage

Your team will have identified any number of threats, large and small, likely and unlikely, controllable and uncontrollable. Now it has to decide what to do with them. Remember that we’re not talking long-term strategy here, but planning a specific, short-term mission. We can control the variables. If it’s a longer-term mission, we’ll have a chance to change the plan.

First, analyze the risks with two questions: what impact would the threats have on the mission, and what is their likelihood of occurring? Use a loose scale—low–medium-high is fine—and let your team discuss and vote on them.

In assessing the impact of the risks, you may want to consider the categories of risk Jim Collins used in Great by Choice as summarised in Figure 10.2 Every mission worth taking will have risks. The ones you want to be really careful of are as follows:

Death line risks, which would seriously damage your team or organization. Don’t bet the house. No surprises there.

Asymmetric risks, in which the downside is considerably greater than the mission’s upside. This is a great reminder to compare the upside and downside. Don’t risk your wall to put up a nice painting.

Uncontrollable risks expose the team or organization to forces or events that it cannot control. If you are going to wake up a sleeping competitor, you better be sure it’s worth it, and that you can control the response.

When you think about it, all of these risks are asymmetric – they are not worth taking, whatever may be gained by the mission. There is really only one question when it comes to risks or threats: is achieving the objective worth the possible price that may have to be paid? If the answer is ‘yes’, then the mission should proceed and the threats, hazards, or risks should be accepted and, if possible, mitigated. If the risks are serious and probable enough, then the mission will need to be put aside. The team will have to set a less risky immediate objective that puts it in a safer place to reach the ultimate objective.

Second, determine whether the threats are controllable or uncontrollable. If controllable, the controlling action will be in your course of action. They will each be mitigated or avoided as part of your plan. If the threats are uncontrollable, you’ll need a contingency plan . . . a what-if.

The lower priority threats are not forgotten. The fact that you’ve taken this step in your planning means your team is aware of these threats. If they arise, you’ll be in a much better position to respond to them appropriately. You will have situational awareness—both about the threats and about the mission situation.

Figure 10: Threat triage

Step 3: Identify Resources to Draw on

Now you know your mission’s objective, and the threats it faces, it’s time to start marshalling your resources and plans to achieve that objective. A little bit of curiosity and imagination, and you may find you’ve got more to draw on than you think.

This stage is a quick pass on resources. Keep your focus on the specific mission and its specific priority threats. What you miss now you’ll pick up then. Get into the habit of thinking quickly yet expansively.

Push for ideas in two areas. First, who have you got to draw on? What skills and expertise do you have there, and how do you access them? Second, what can you bring to the mission? What funding, spaces and places, plant and equipment, systems and technology, supplies and material?

Your organization will offer you more resources than you think. To know what’s on offer, know your business; know your organization. Talk to people, listen to what they say. Understand what they do. Ask how you might be able to help them do their job more easily. That will help you understand what they do now, and what they can do in the future. You never know if that’s a resource you may be able to draw on.

Situational awareness of your own organization will offer up more resources than you imagined you had. Those resources can be multiplied by considering people outside your own organization: your clients, relationships, alliances, and communities. Any relationship you have is a potential resource. Be willing to help people, and they will be willing to help you.

With people come valuable resources, tangible and intangible. But you might want to run down the following checklist of tangible resources to see what you really have to hand. At this stage, you’ve considered your objective and threats, so it’s best to have these squarely in mind when considering resources. Otherwise, you’re free-forming a wishlist of things you may never need.

Your tangible resources will come from these categories: finance (money or exchange), technology, human capital, mechanical and business systems, equipment and tools, supplies and materials, land and facilities. Run through that list and consider whether anything you have access to will help you either meet your objective or beat your threats.

Step 4: Evaluate Lessons Learned

You’ll know as well as we do that there’s a big difference between data and knowledge, and between knowledge and wisdom. I may know some facts, and I may know how to do things that involve those facts. But am I wise enough to make the right decisions with that knowledge? Truly knowing the difference is a nirvana that seems to have been beyond all but a few organizations—a knowledge system deep enough to hold what’s needed, and simple enough to access it.

With Flex, most of the lessons learned have come from the immediate past. Don’t forget, each mission is debriefed and generates lessons learned for the very next mission, which become part of the standard operating procedure then and there. But other lessons learned are for less common events and contingencies, and so need to be stored away in the standards to find later.

If time and resources are important to your organization, your team needs to dig out that deeper experience and do it fast. Three questions will take you there:

- What standards are relevant?

- Is there relevant experience in the team?

- What relevant experience can we tap into outside the team?

‘Relevant’ is the word here, especially for lessons from outside the team. As with resources, the lessons you’re after are only those that will increase the chances of mission success or help you avoid a threat. You’re tapping into a team that knows its business, and knows its history—it has situational awareness—so allow it to tap into its experience and memory.

One of the lessons that will almost always be relevant, is to deal with the person, not only the facts. Well-known across the pharmaceutical and FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) industries, is the Tylenol lesson. In October 1982, seven people in Chicago died after taking Tylenol capsules, the then leading painkiller in the U.S. Someone had put cyanide in bottles on the supermarket shelves. Johnson & Johnson might have tried to deal with the emergency undercover. Instead, they removed and destroyed 31 million bottles nationwide, led the introduction of tamperproof packaging and caplets, and kept the public and authorities fully informed. It’s a lesson of responsibility and success that still resonates. But keep your hunt for such lessons tight.

There is one lesson, though, we always keep at the top of the list—Hofstadter’s Law:

‘It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.’3

Step 5: Assign a Course of Action

Here’s where all the thinking from Steps 1 to 4 comes together in the actual course of action. Getting to this plan reflects what Flex planning is all about: fast, yet considered; diversity in thought, yet a team. Similarly, the course of action reflects what Flex plans are all about: simple yet dynamic; direct yet empowering.

Is this process about nailing a plan in one hit? No. Each step suggests a threat, which requires an assessment, which demands a response. As each step is identified, you’ll think of the resources and lessons to make that step a certainty rather than a hope. It’s all about testing and re-testing, to iterate and improve the plan, quickly and efficiently in the available time.

What is a course of action?

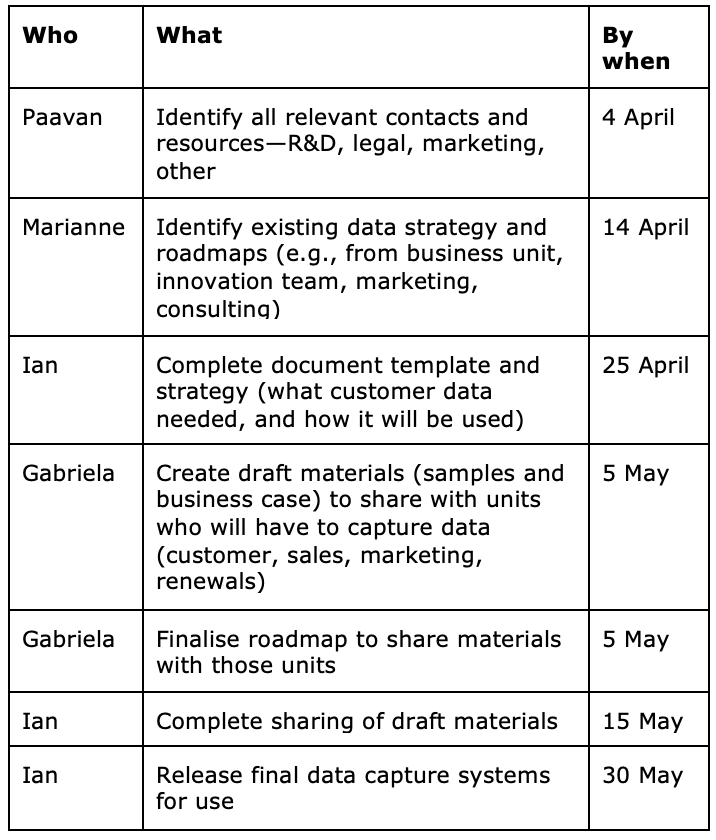

The course of action is essentially a simple three-column list that sets out a series of tasks, each assigned to an individual, to be done by a certain time: who does what by when (see Table 4). It includes decision points that may trigger different tasks or options, or allow tasks to be skipped. But it does not include how these tasks are to be done, nor state the obvious, nor restate standards.

A list of tasks

The team will need some form of logic to help identify tasks that will reach the mission objective. The military would think of the lines of operation that are needed. For example, if the day’s mission was to take and hold an area of contested land, there would be tasks assigned to various combat, logistics, and communication units. But if the mission was to hold a large area of contested land with a big civilian population, the lines of operation might include counter-insurgency action, humanitarian action, governance capacity, water infrastructure, telecommunications, shipping lanes—a whole host of responsibilities that need to be independently managed, yet have a common purpose.

Table 4: Clear course of action

Decision points on the timeline

A Flex plan is dynamic, which it won’t be if it demands certain actions at certain times. There needs to be flexibility. We don’t know everything at the planning stage: we don’t know the effects of our actions and don’t know our competitor’s every move. So we need decision points along the way, forks in the road that make us pause and consider.

There are three types of these decision points, each very different in nature but critical to the mission, that is part of the course of action. They are expected events, controllable threats that are realized and regular team check-ins.

Expected events. The first on the list are decisions to be made when we get to an expected point. A takeover target or raw material may have reached a trigger price point. The team is expecting to make that decision, and either has the information it needs to make it or knows where to get it.

Controllable threats. The second set of decisions are triggered by threats that your plan hasn’t yet controlled. You’ll never really know the timing of these triggers, though you’ll have an idea. Ideally, you’ll have a lead indicator: something that says the threat is about to be realized. If it’s a threat you can control, you’re still on your course of action.

Regular team check-ins. The third set of decision points aren’t on the course of action but are part of your plan. These are the team’s check-in points, and their intervals make up the mission’s execution rhythm. If your mission is staged to take two months, you might be checking in weekly. If your mission is over in a day, you might check in every hour or so.

Process for creating the course of action

What you’re aiming for is a course of action that is as clear as possible, for which each step is as simple as possible, and each step is assigned as an individual task. Who does what by when? To get there, one Flex approach when the planning group is large enough—say 9 or more people—is to split it into three groups working independently, then bring their thinking together.

Using three groups rather than planning the mission with the whole team together has a number of advantages. Everyone gets involved and contributes—you don’t have people hogging the air time, without perhaps more thoughtful team members having a say. You also have a greater chance of avoiding two common group errors. ‘Groupthink’ is the more familiar one: where everyone gets behind a poor plan because that’s where the energy is, and nobody wants to stand in front of a rolling train with an alternative view.

So brief the whole team to prepare a course of action, before splitting them into three groups. Brief them by reviewing the first four steps: the mission objective, and its relevant threats, resources, and lessons. We want the three plans to be different. We are looking for creative ideas, options to overcome the same hurdle, different routes to the same endpoint.

The final step is to resolve the three plans into one plan that the team will support. The mindset here is not to select the best plan, but to create a single plan from the best ideas of the three. Each team presents their plan to the other groups so that the nature and purpose of each step are clear. To start, choose the easiest to read, cleanest, most comprehensive plan—usually one of the ‘constrained’ plans. Mark its tasks as an action (A), a contingency (C) or delete (X). Switch to the next plan, and work through its steps to see if anything can be added to the first (A or C), or if any of the existing steps could be altered, or their order changed. Then the same for the third plan. Finally, have a look at the resulting final plan, to consolidate and clean up the steps, and see what gaps or threats remain.

Red Team review

It would be a remarkable achievement for your team to come up with the perfect plan for a complex mission in a single planning session. It’s a difficult task, made more difficult by the inherent tendency for teams to rely too much on their own knowledge and be a little too optimistic about the outcomes. What you need is an outside view. Instead of launching the plan and later having a post-mortem on its marginal success, have a fresh set of external eyes test it out thoroughly before you start. They’ll think of threats you won’t think of, and test that the whole plan rests on a baseline of realistic data and assumptions. Remove the planning fallacy of optimism. Bring in the Red Team.

The Red Team has had a long history in the U.S. military. Most recently and famously, it was used in planning the successful Navy SEAL raid on Osama Bin Laden’s hideout at Abbottabad—Operation Neptune Spear. An entirely independent, outsider’s view of a strong yet risky plan made it that little bit stronger and less risky. Now, it’s no trivial task to bring in a Red Team to critique a team plan, without offending the team or raising hackles that may take a while to ease down. So, there are tested rules to amp up the value of the Red Team while minimizing background noise. They apply to Red Team identity and process.

The Red Team should consist of two to five people who are external to the planning team. They cannot be present in the game, but they need to be helpful, to want the mission to succeed. They need to know the context and implications of the mission, with experience in similar operations or markets—ideally with the differing perspectives of customer, competitor, vendor, regulator, etc. In our language, they should have situational awareness for the mission, and be able to suggest additional threats, resources, and lessons learned.

It’s essential that the Red Team session is held in person or over a live video link. Hold the Red Team session in a room with minimal distraction, so that the focus is on the plan and the plan only. Have two of the planning team ready as scribes. Brief the Red Team on what’s needed from them: alternative perspectives on the assumptions, actions, threats to and effects of the mission. The planning team leader presents the plan visually—in charts and writing—the team leader guiding the Red Team through it, but not talking over their reading and thinking. Then wait.

The Red Team should ask the clarifying questions they need, then offer comments in rotation, one after the other, until they have no further comments to offer. The two scribes work in rotation also, so as not to miss anything when the comments flow quickly. Each comment is offered with the phrase ‘Have you considered . . . ?’ That is the question. This session is not a debate over whether or not the plan is a good one. It is only to consider additional thoughts on the mission’s assumptions, actions, threats, and effects.

After the Red Team is thanked and dismissed, the mission team addresses each comment in turn and adjusts the course of action if needed. That’s all it is. The term ‘Red Team’ has taken on a lot of specialist meanings for organizations and individuals who ‘specialize’ in red teaming. But in Flex, its role and commitment is very simple. We are just looking for an unbiased, experienced, valued opinion. There is no preparation or specialist expertise needed. Just be in the planning room for the Red Team session.

Step 6: Confirm Contingency Plans

By now, the only thing you haven’t planned for is the threats that you cannot control. Your team needs to be able to answer every what-if it can think of, and be ready to respond to it. Respond, not react. Having thought of responses, you are already ahead of changing conditions. If you have to react to unknowns in real-time, you are already behind.

As pilots, we work the what-ifs hard, to be one step ahead in an action. What if the air refuelling tanker doesn’t show up? What if a ground force needs our assistance more urgently than we need to take out our target? We like to say that flexibility is the key to airpower, and preparation is the key to flexibility. In fact, because we know our standard procedures so well, and we know the likely plan for most missions, about 50 per cent of our planning time is spent on these contingencies.

Your contingencies will be just as challenging. What if one of your team hasn’t turned up? What if one of your audience takes offence, or is just grumpy, and really starts to interfere with your meeting? It’s much easier to brainstorm these possibilities beforehand than it is walking up to the client site in a heatwave with an armful of materials, or facing a boardroom of hostile investors, or a conference hall of alarmed employees. Every client and employee loves someone who has thought ahead to cover things beyond their control.

Practice contingency plans carefully

You’ll know that these are not fanciful possibilities. Stuff happens. A product launch and the star celebrity doesn’t turn up. Who or what’s going to take their place? Is it a fill-in celebrity, a cross-over to a live feed, or a product launch that doesn’t depend on a celebrity? Keep peeling back what could go wrong, until there’s nowhere else to go.

Importantly, be ready for your contingency responses even more automatically than your expected course of action. Learn them, practice them, remember them. Why? Because a contingency that hits is almost by definition a potential disaster, and that disaster will be playing on your mind. You’ve done all this hard work and planning, and now it’s on the line.

Contingency–trigger–action

To be ready for a what-if, Step 6 asks you to clearly define three things:

- The contingency, or uncontrolled threat

- Its trigger—when you know that the threat has become real, and

- Your action—what your team will do in response.

Most threats will have two triggers: a lead indicator that warns you the threat is likely, and a lag indicator to announce it’s arrived. You must have a response to a lag indicator, and a response to a lead indicator is ‘most advisable’. Again, the weather provides a simple example. Rain is a potential threat to a sales event. Your lead indicator is a 24-hour forecast that it will bucket down. Start putting your alternative plans on standby. Your lag indicator is the rain itself. Too late to think of what to do then. Lucky you already have.

By following and actioning this six-step planning process, you are ensuring the success of your mission. Surprises happen, but a Flex plan has already found the solution!

References –

1 Walt Kelly was nodding to a line from 140 years earlier. After the fledgling U.S. Navy defeated and captured six British vessels in the 1813 Battle of Lake Erie, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry reported back: ‘We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop.’

2 Jim Collins and Morten Hansen, Great by Choice, HarperBusiness, New York, 2011.

3 D. Hofstadter: Gödel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid. 20th anniversary edn, 1999, p. 152.

4 D. Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 2011.

No Comments