08 Sep The Flex Engine: Getting Things Done

Flex Planning

Fighter pilots hate surprises! It’s hard enough hanging onto a jet at 700 miles per hour and 9 G. It’s enough to fly formation, work the radar, listen to calls and monitor the dials and displays. It is harder still in combat when tracking multiple targets, being locked onto by enemy craft, or dodging a surface-to-air missile. The last thing you need is something to come out of nowhere, something you really have to think about or you’ve lost your ass. There is no time to think. The time for thinking is on the ground! Flex planning allows for thorough planning on the ground, so we are successful in the sky.

Yet surprises do happen, and they can be nasty. Or, on the positive side, we might see the opportunity to pack a little bit more into a mission, to help out a unit on the ground, or take out a target that’s come into view. We need the headspace to think when our operating environment changes. So the mission plan needs to be simple enough for us to take it all in at the briefing, but dynamic enough for us to respond when we need to.

That’s why we plan missions thoroughly. It’s not enough to know what to do, all going well, or even what to do if something goes wrong. We have to plan for every threat, for every contingency that any one of the planning team can think of. We want to minimize the things that can take us by surprise. That way we can respond as planned to things that pop up and have the headspace to think if something completely unexpected happens.

Does that sound like your latest project, negotiation, or presentation? Well done if it does, truly, you know what it takes to get there. But for most of us in business, it sounds unrealistic. If we did that much thinking, we’d never get anywhere, right?

But Flex companies do! What we’ve described above gives the impression that planning occurs in isolation. In reality, it is part of a cycle. You’ve just completed a similar mission, and you’ve debriefed on what worked and what didn’t. Yes, you have to plan for every contingency, but you’ve done the same thing last cycle. You know what is likely to happen. This becomes standard practice. You have to assume your team knows their standard practice. Remember: standards are your wings. You can’t fly without them.

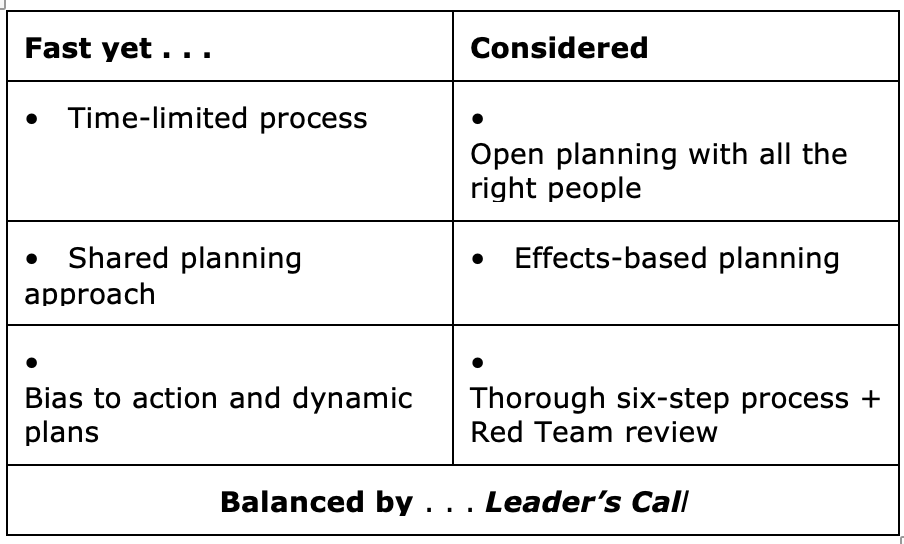

In fact, the secret of Flex planning is the way it balances three seemingly opposed sets of things. The Flex planning process is fast, yet considered, so that you have an effective plan when you need it. The resulting Flex plan is simple, yet dynamic—so that it nails the objective, changing as it needs to. And for those executing the plan, it is direct, yet empowering—so that they have clear accountability while being allowed the leeway to take the initiative they need.

Planning: The First Stage of the Flex Cycle

Planning is the first stage in the Flex cycle, and it sets both the tone and the direction for the rest of the cycle. You brief the plan, the mission is the brief, and you debrief against the plan. So, we’re spending a little more time on understanding how the Flex way of thinking is harnessed at the planning stage because that will flow through the rest of your performance.

Flex planning—fast, yet considered

One of our colleagues, ‘Thor’, embarked on an Executive MBA program soon after retiring from the air force in 2014. It was an intimidating class, full of bright young sparks and experienced hands, both looking to finesse their management skills. As in all such programs, teams had to work together in game-playing assignments, looking to outmaneuver other ‘companies’ from the same class in a hypothetical market. Thor was deeply impressed by his classmates’ level of analysis and their ability to articulate it. They could out-think Sherlock and sell ice to an Eskimo, no doubt about it! So they laid out their points of view and got ready to make their play. And ready. And ready. They got so close! Just a little more analysis. Ready, aim, aim, aim . . . a little more discussion . . . aim, aim. But they just couldn’t get ready enough to say ‘Fire!’

For Thor, this was a real eye-opener on the reality of organizational decision-making. People had the data, had the analysis, but didn’t move. Even in the friendly, hypothetical market of the MBA classroom, hackles were rising. Opportunities passed by. Other teams got ahead. As the classmate with the least experience in corporate decisions, as much as he wanted to, Thor didn’t feel he could push his team over the line. Finally, he could hold back no longer. He asked the team if they’d heard of a bias to action: the idea that inaction itself is a decision, and most often not the right one. The idea is that by taking action, new opportunities come up, new questions arise to answer, and new things come to practice. As long as the action wasn’t fatal and was pointing in the right direction, go for it!

Blank faces among classmates is not a pleasant experience. No one was offended, but they took it courteously as an interesting perspective to add to their analysis, to which they returned. Just as Thor sank back into his chair, defeated, he noticed someone smiling across the circle. One of the classmates was an ex-Navy SEAL—who was thinking the same thing and had finally found a soulmate. A room full of ponderers was no match for two people with a bias to action. Together, they got things moving!

Bias to Action – The Antidote

If taken sensibly, this bias to action is the antidote to paralysis by analysis. It is a bias much needed in fields of technology, for example, that hire graduates well versed in accessing, manipulating, and analyzing data, but less so in making the decisions on which that data is based. And that’s a large proportion of the highly skilled, educated workforce we rely on!

By bias to action, we don’t mean an urgency to crash through or crash. We mean an appreciation that the mission is upon us, that planning time is finite, and that clear decisions are needed. The team leader has to make a timely call.

So, how can Flex planning be fast, yet still consider everything it needs to be for an effective plan? To keep things moving, Flex relies on:

A known, shared, time-limited process. This is for both our strategy and mission planning. Everyone knows the steps and what each step is aiming to reveal, and so each discussion is focussed and works through what it needs to in the time available.

Bias to action, acknowledging dynamic plans. A Flex plan assumes that action needs to be taken sooner rather than later and that the team itself will be making some decisions once that action starts. Bed down what you can in your planning time, then trust the skills, situational awareness, and initiative of your team.

This combination reduces the time you spend on your planning so that it doesn’t start to cut off options to act!

Flex Planning is…

Fully considered

Flex planning needs to be fast, but your Flex plan still needs to be considered and effective. The four elements that will help make sure it is are: the right people taking part in open planning, taking part in a clear six-step process, focussed on the effects of the actions, and being independently reviewed by a Red Team.

Open planning: Open planning means that all the right people are taking part in the planning like the people responsible for executing the plan, a more senior ‘champion’ who can resolve resource and conflict issues for them, and situation experts or specialists. Open planning, as in whole team planning, or ‘teamstorming’ as we call it, is one of the disciplined collaborations that makes Flex work. Every person who is part of the mission is part of the planning! If you need more specialists, bring them in. The more diverse the group, and the more perspectives, the better. Fighter pilots don’t plan on their own, they bring in specialists from intelligence, maintenance, weather, weapons, and terrain who can contribute to ‘building the picture’ or have the situational awareness they need. Importantly in business, if the plan includes how you deliver what your client wants, think about including your client in the planning! That’s how we deal with complexity—build understanding across departments, and engage people from different generations.

Six-step planning process: This time-limited process is rigorous so that all contributions are captured in an orderly way that leads to a clear course of action. The process starts with identifying the team’s objective and ends with a watertight plan for how to achieve it. It considers threats, available resources, and lessons learned. It lays out a clear course of action, ready to be briefed, and an execution cycle for keeping on track.

Effects-based planning: This means that the planning and action will meet the leader’s intent: a resulting effect that will take the team and its organization one step closer to its intended destination! The leader has to decide that intent before asking the team to plan the mission so that the mission objective is sure to pursue that intent. It’s an essential preliminary step in our planning process.

A Red Team review is the last stage of our planning process. The Red Team review means that the whole plan gets stress-tested by a totally fresh set of experienced eyes. If a key specialist cannot be included in the planning team, make sure they’re in the Red Team.

Flex planning works in good time because its processes offer a tight balance between speed and deliberation (see Table 1). They really tighten the gap between ‘close enough is good enough’ and 100 percent certainty. But you still need to make a call that you’re ready to act. That call is the leader’s judgment.

Table 1: Flex planning is . . .

Apollo 13: A two-minute planning lesson

Not everyone can sit in on a military planning session. If you don’t get that chance, have another look at the scene from the movie Apollo 13 known as ‘A New Mission’. It happens pretty quickly, but it’s all there. Shortly after Tom Hanks beams in with ‘Houston, we have a problem’, all the flight engineers at Mission Control are brought together. Ed Harris as mission commander Gene Kranz switches to ‘failure is not an option’ mode. He needs everyone there: it’s open planning.

‘OK people, listen up! I want you all to forget the flight plan. From this moment on, we are improvising a new mission.’ The objective is to get the astronauts home. The threats are many and obvious. They identify the only engine capable of keeping the spacecraft going and revisit what they know about it. Ideas are tossed up and thrown aside, and it starts looking impossible. The urgency adds pressure and makes it look more impossible.

Kranz ignores the fuss and the overhead projector that inevitably doesn’t work. He makes the call on the course of action—a slingshot around the moon. The engineers start work on sub-plans to meet the many threats, among them that the capsule will run out of power well before reaching the earth.

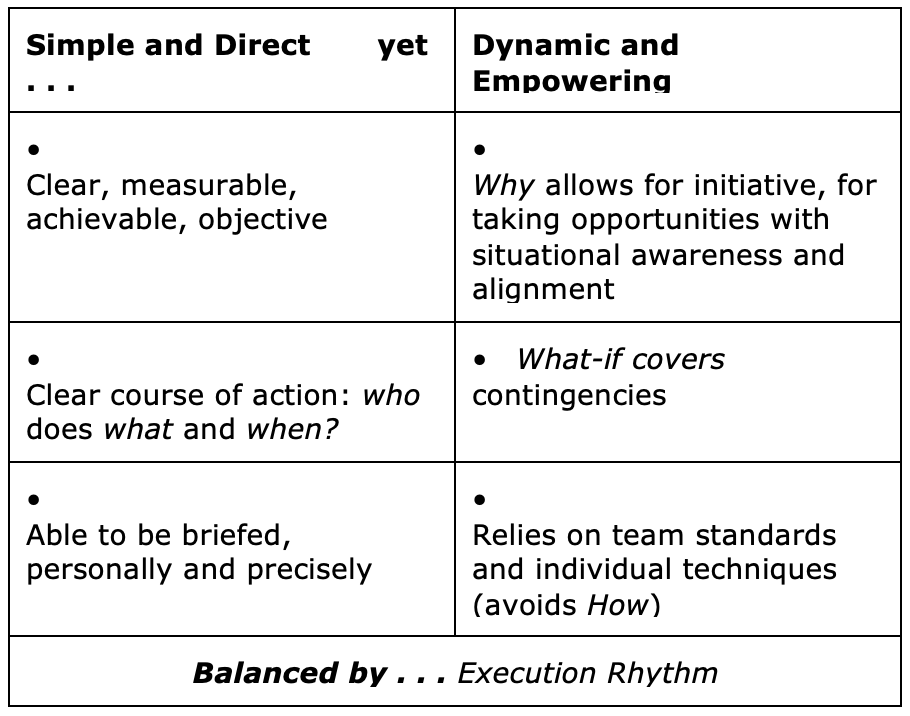

Flex plans—simple, yet dynamic

The more complex a plan, the more likely it will fail. The more steps it has, the more detailed the instruction, the greater the chance of human error. A simple plan means that the people accountable for it are absolutely clear on who does what and when.

Flex calls for a little more, and that little more makes all the difference. We can put it in the same simple terms:

A Flex plan answers who, what, when . . . and why and what-if.

These two additional little questions carry a lot of weight!

Answering why? means not only confirming the mission’s immediate objective but also why it has that objective. For now, it’s worth bearing in mind that any mission plan needs to take into account three potential outcomes: its primary operational objective, the effect the mission will have on relationships with people that matter and the effect it will have on the learning and culture of your own team.

Answering what-if? makes sure that you’ve thought of the threats, the things you can’t control that have a greater or lesser chance of happening. These include, of course, the threats to that social effort: the reactions and resistances of the people involved. But keeping the ‘what-if’ separate achieves an extremely important outcome: focus. So, often in our planning workshops, we see teams argue about ‘what-if’, so that the first task of any possible plan wilts on the vine before seeing the light of day. Yet, the world is an imperfect place, and we need to test our plan against the things that may go wrong. As they say in the squadrons: ‘Plan for perfection, prepare for the worst.’

These two questions—why? and what-if?—are what makes your plan dynamic, able to respond to changing conditions and realities as you execute the mission. It engages people to achieve their mission and makes the plan both threat- and time-sensitive. If a team has situational awareness and knows why they’re on the mission, they can adjust their plan so that it still delivers what’s needed, if at all possible. And if it’s not possible, they can abort the plan. A Flex plan calls on your team to be engaged in their mission, not robotic.

If you never need to engage people, if you never need them to react to a change in circumstances, then don’t plan the mission—just write out your step-by-step procedures and get your robots to follow them. But if you try that with people, don’t expect them to follow your lead for long.

There is a distinction to make here. When we get to executing the plan, you will want to draw on checklists and standards—fixed routines that you know work, that calm you for action, and that free up your mind to make decisions that matter. They may be the company standards or procedures that have to be followed. They may be your own techniques that you’ve developed and trust, and that your team respects. But these are not part of the plan—they’re your wings, what you rely on when you’re in action.

Balancing Simple and Dynamic: The Execution Rhythm

At some point in the planning process, as the contingencies and the variables mount up, the plan will start to lose its clarity. There are too many what-ifs, too many options for people to take, too many possibilities that may change the game.

How can a Flex team keep that balance? By setting what we call the ‘execution rhythm’ for that strategy or mission. Every mission and strategy has an execution rhythm (see Table 2). The rhythm is the time span after which the team needs to check in to see that it’s on target and that the plan is working. For shorter missions, that may be the end of each day or the end of the mission.

For a mission that’s any longer than a week, you’re going to have to set an execution rhythm as part of the plan. When will it make sense for the team to come back in and review their progress against the mission objective, or to start on a new plan for a new mission objective? A plan should not try to layout its course too far into the future. There are too many unknowns! A strategy can look into the distance, knowing that a host of mission plans are needed for the strategy to be fulfilled. But each mission plan must keep its execution rhythm tight.

Table 2: A Flex plan is . . .

Flex plans—direct, yet empowering

There is no waffle in a Flex plan. The whole point of it is for people to know exactly what they need to achieve by when, for every task in the plan. In that sense, every task is stated as its own mission objective, and the same rules apply: it must be clear, measurable, and achievable. And so it will become part of a Flex brief: direct, personal, and concise. So how does any of that empower anyone?

We cannot emphasize two characteristics of Flex planning enough. People are working out their own plans, and those plans do not include how to do things. These two characteristics have long been consistent with better motivation and performance at work. In the 1980s, several studies showed that people worked harder, were more satisfied, and trusted their employers more if their management supported their autonomy: respecting perspectives, giving choices, and encouraging self-initiation rather than specifying how they should do things. For the millennial generation, support for autonomy is even more important. Millennials will be more energized and productive if they have greater autonomy over where, when, and how they work.

The team’s own plans

Flex plans are created by the teams who are responsible for executing them. In being part of their team, in taking part in their planning, people are signing up to the team’s plan. They are making commitments to their team, and the Flex experience is that those commitments will hold.

In The Upside of Turbulence, another book that helps leaders deal with complex times, MIT Professor Donald Sull suggests that ‘The best promises share five characteristics: they are public, active, voluntary, explicit, and they include a clear rationale for why they matter.’ Each of these characteristics is shared by the commitments made in Flex planning. When a team works together to set its mission plan for a worthwhile, aligned objective, the team members have no problem buying into the plan or being responsible to take on the needed tasks. If anything, the team needs to watch for people who overload themselves with tasks.

Only Include What’s Needed

A Flex plan does not go into the detail of how its tasks are to be done, nor state the obvious, nor restate standards. Just like the strategy, the mission is defined only by its intended effect: the what. Similarly, each task in the mission plan is defined only by its intended effect: what by when by who; clear, measurable, achievable. How that result occurs is up to the team for the mission or the individual for the task.

So if your plan calls for Tom to have a car outside 1135 North Street at 11 p.m., it’s Tom’s task to get it there. You don’t want to get into the route taken, the speed driven, the need to obey traffic laws, the need for fuel. You don’t want to worry about the way Tom drives. Your team will have standard operating procedures (SOPs). It’s obvious the car needs gas in the tank and air in the tires. These are ‘breathing’ steps: steps so obvious it’s like telling people to remember to breathe. Beyond that, leave it to Tom to drive the car his way, using whatever techniques and preferences he likes—and that is consistent with the SOPs. If you go into too much detail, if you belabour the obvious, it’s an insult to people! They’re on the team to do these things—let them work it out, or ask for support.

As Charles Duhigg said in The Power of Habit: ‘Giving employees a sense of agency—a feeling that they are in control, that they have a genuine decision-making authority—can radically increase how much energy and focus they bring to their jobs.’ Or, remember how General Patton put it: ‘Don’t tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do, and let them surprise you with the results.’

Not your typical plan

Some of what we say about Flex planning will be familiar to you from your own experience. But we would be very surprised if the whole process is familiar, more so if it is a process you’re following now. Here are some of the differences we find when talking about planning with our clients.

For starters, most planning is done by people other than the team that is going to execute it. The more complex the task, the wider that gap becomes. There are planning and project management specialists who are tasked with degree-demanding software to work out ‘the plan’. There are strategy teams who sit apart from operating divisions to work out ‘the plan’. Even in small groups, team leaders work long into the night to figure out exactly how their team will work, without including their teams in the plan. Flex planning ensures a realistic course of action because the people setting the course are the people (or their teams) who will be running it.

Second, most planning starts by looking back: by rolling out the plan from last time. If it worked, it can be repeated, no? By rolling out the last plan, you’re also rolling out all its assumptions about the context, threats, and resources available. It may or may not work, but it will never get better! Instead, Flex planning starts with the future: it looks forward to the mission objective. With that single peg holding down a clean sheet, the team can look without distraction at what they have to do, what they have to help them, and what may stop them.

The next most obvious difference is the amount of analysis that goes into Flex planning. If you’re updating the last plan and then handing it to the ‘doers’, there isn’t really that much consideration of new data and current affairs. Flex teams know the purpose of each step in the course of action because they’ve put it there to get one step closer to the mission objective, or to address a threat.

We deal with threats in the plan. Most plans set out a solid string of actions, and then have a section called ‘risk management’. These are additional steps that are likely to be needed but are held apart from the main flow. In Flex planning, if a material threat can be controlled in any way, that control is part of the course of action. That way, we know the course of action works as a whole with or without those threats. If the threat is uncontrollable, then a contingency plan will come into operation at a decision point with a known trigger. There are no floating risks left as part of a risk management plan that may never be reviewed until it’s needed, when a review is too late.

Flex planning only stops when the mission stops. It is continuously adapting to realities, which the team leader continually reviews. It continues through to the moment of the brief, pauses only to start the mission, and then continues right through it.

Flex Planning References –

E.L. Deci, J.P. Connell and R.M. Ryan, ‘Self-determination in a work organization’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 1989, 74, pp. 580–90. Quoted in Gagne and Deci, ‘Self-determination theory and work motivation’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2005, 26, pp. 331–62. http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/1989_DeciConnellRyan.pdf

PwC 2015, Millennials at Work: Reshaping the workplace. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/financial-services/publications/assets/pwc-millenials-at-work.pdf

Donald Sull, The Upside of Turbulence, HarperBusiness, New York, 2009

Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit, Random House, New York, 2012.

No Comments