30 Sep Execution – Keeping People to the Plan!

Now that you have briefed the plan, it is time to fly the brief! Execution. One reason that few plans survive upon execution is that people are human and don’t always stick to the plan. People lose focus, get overwhelmed, think that the situation has changed when it hasn’t really or, for whatever reason, they just make mistakes. Most often, that’s due to task saturation—too much going on, too much interference and interruption for one mortal to manage. Alternatively, accidents happen when there’s not really much going on, not enough to keep the mind active and focussed.

How People Lose Focus During Execution

We all know what it feels like to be overwhelmed, to lose focus on doing the important things, and to even lose track of what the important things are. Our minds just can’t take it all in. Surprisingly, though, it’s more common for us to experience a lack of focus when our minds are, quite literally, bored from inactivity. No matter how good a book or a film or a storyteller is, you might find your mind drifting off to other thoughts. That’s because your mind can absorb information far more quickly than the speed of normal reading or speech. So the trick is to feed the mind just enough information for it to be fully engaged, yet not overwhelmed. That way, you can avoid both the sophomore and the saturation risks.

The Sophomore Risk

Sometimes, people who ought to know better just aren’t paying enough attention to what’s going on. Overconfidence leads to cut corners, false assumptions or just bad judgments. Research into air force accidents reveals a curious statistic. Errors are more likely to be made by pilots with four to seven years’ experience—not the new or ageing pilots you might expect.

Pilots are building up their skills and experience all the time. Unfortunately, though their confidence and lack of focus rise even more steeply. When they begin, they’re fully engaged in the new experience, and can make quite good decisions while facing very new situations – what many call ‘rookie smarts’. But from four years in, they’re in a danger zone—until they come to their senses and again realize you have to pay attention if you’re flying a 45,000-pound machine with 50,000 pounds of thrust at 1200 miles per hour. Maybe they’ve had a couple of close calls, maybe they learn from an error of a classmate—hopefully, it wasn’t fatal.

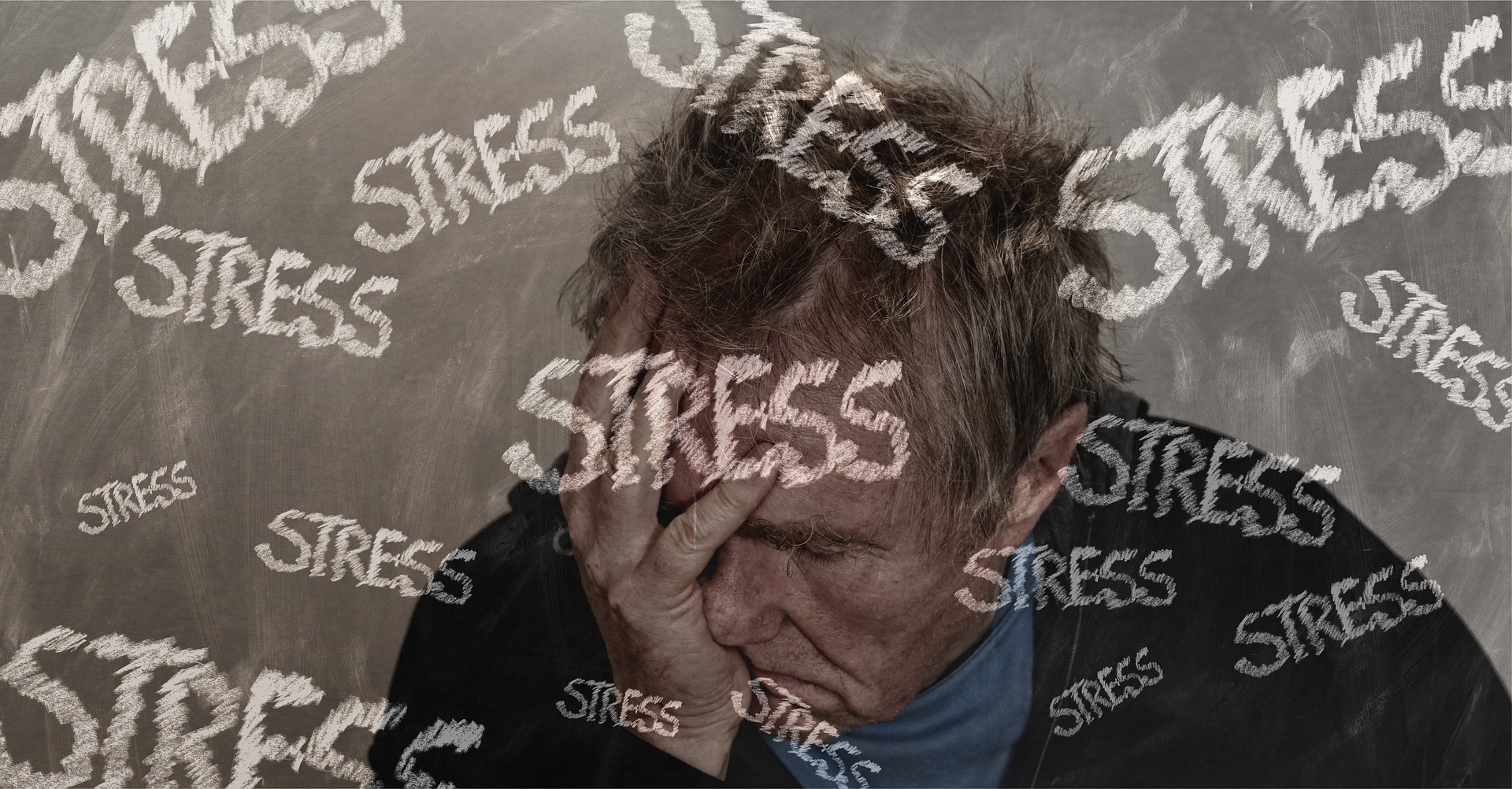

The Saturation Risk

The standout, biggest risk to flawless execution—to any execution—is what pilots call the silent killer: task saturation. It is totally avoidable and insidious by nature. You have to watch out for it, to be able to recognize and respond to it. Task saturation is the perception that you have too much to do, in not enough time, with not enough tools or resources. Whether that feeling is real or imagined doesn’t matter. Once it takes hold, you will not act the way you and your team need you to. You will let someone down, or worse.

In business, too many people wear overwhelming ‘busyness’ as a perverse badge of honour. The all-nighter before the killer presentation. Being three places at one time—two virtual, one physical—with those in the room with you getting the least attention. The cross-continent flights to chase one more meeting, to make up for the problem that was someone else’s fault. That’s one hell of an important person right there. It feels good to be so valuable. As task saturation increases, performance decreases; that errors track saturation like ants track honey. Task saturation in business is a sugar hit; it’s nothing to be proud of.

Pilots learn that lesson the hardest way of all, seeing a comrade and mate lose their life for no good reason. Murph lost two close friends who flew perfectly good jets into the ground. Didn’t see it coming. They were good pilots, and if you asked them how they were five seconds before impact, you’d have got a smiling thumbs up. But they died task saturated, and never knew it.

Spotting Task Saturation During Execution

Understandably given the stakes, the U.S. military has done a lot of work into recognizing when someone is getting task saturated upon execution. The work wasn’t necessary—pilots are asked what they do when they feel stressed, and consistently say the same thing—but it did hammer home the anecdotal. What do people do when they feel they have too much to do with the time and resources they have? First up, the good endorphins in our body kick in, and we feel good, energized, ready to climb that mountain and skip down the other side.

It’s a great feeling, but it lasts as long as this sentence. Before long, our bodies natural ways of dealing with stress get oversaturated. The nervous tension locks you up, and you’ll do one of three things: you shut down, you flitter from task to task, or you fix on one thing and one thing only. Trouble is not far away.

The first and most harmless coping mechanism is to shut down. You look at your desk, your emails, your to-do list, and just go blank. Anything else becomes more important, no matter how trivial, as long as it’s not part of that mess. Go for a walk, visit the gym, do your monthly receipts, play a game on the smartphone. That’s fine every now and again, we all need a break. You might even be happy about it and walk about the office looking for a pointless chat or an evening drinks buddy. But when the next day ticks over with no change, check-in with yourself—is this OK, or have you shut down? Any luck, someone will have already noticed. The one good thing about shutting down is that it’s easy to spot.

Flitterers, on the other hand, are bad news. They’re risky because they act busy but do little, and kill you while they’re doing it. Everything they do is part of their job, and they’re not shutting down. They’re not waving that flag that says ‘It’s all too much for me’. But they’re not doing anything important, and not finishing anything at all. Compartmentalizers are specialist flitterers, flitterers with form. Have you ever wanted to get everything in order? Just put everything into nice, neat, calming piles and lines while just beyond your vision the world is burning? Rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic?

Compartmentalizers will make lists, re-plan their project (again, by themselves), file papers, go from top to bottom, and become obsessively linear. Again, that’s OK as a regular routine, keeping things in order so they never get out of control or need a year’s cleanout. But if you’re doing it when your team really needs you to be doing something else, then there is a problem. And the sign is that you’re letting a team down in an uncharacteristic way: a missed deadline, a late arrival, or communication that just doesn’t make sense.

Finally, there are the channellers. As the name suggests, channellers have tunnel vision, focussed or fixated on one thing to the exclusion of all others. Most of us are potential channellers when things go wrong—80 per cent of all people—and the examples are almost too many and too painful to recall. The cable company that was so determined to plant their new advertising campaign on the airwaves that they didn’t think through whether their connection staff were able to meet the new demand.

The Dashboard

The dashboard is critical in execution for pilots. It has all the indicators you need to see, in a hub-and-spoke layout. The centre hub is the primary indicator. For pilots, that’s the attitude indicator or ‘artificial horizon’. If you can only do one thing, focus on this and adjust your wings to keep the plane level. The secondary indicators form the spokes. They’re all important indicators of the plane’s performance, so a pilot will scan the dashboard constantly, and every scan passes over the centre hub. It’s the hub-and-spoke layout of the cockpit cross-check.

Many businesses use dashboards, but there are three standout features to the cockpit-style dashboard that aren’t often seen. First, the primary indicator is the largest image and is at the centre: you can’t miss it. Second, all of the indicators are visual: You don’t have to read anything when your eyes are rattling. You can quickly scan across the dashboard and see that the indicators are where they should be. Third and most importantly, if the indicators are not where you want them, you will know what you should do to adjust, correct, guide, and get the indicator back where it should be. For each dial, there is a corresponding action to take to move the needle.

Your business will have its own key performance indicators, and these will make up the company’s dashboard. Because it’s the CEO’s dashboard, it will show the CEO’s priorities. The main thing is that it is clear to the person using the dashboard what action to take to get the indicator level to where it should be.

Should everyone in the company be focussing on that dashboard? No. People at different layers and within different teams will have their own missions with their own objectives for execution. The indicator that shows whether their own objective is being met should be that team’s primary indicator. Other indicators should reveal factors that may contribute to that objective. Many companies want their employees to have one universal dashboard. But that implies everyone in the company should have the same priorities as the CEO. Would that distract them from their daily mission, the one they’re assessed and paid on? You bet. Keep it on the side, but not the centre. It’s not their priority.

Clear, Concise and Certain Communication

There are times for chewing the fat, and teams love them, but not when everyone’s under pressure for precise execution of the plan! When there’s a lot going on, a lot of it uncertain, you can’t afford long rambles and you can’t afford short statements that are unclear. Clear, concise statements also help you and those around you to keep focus. Ramble on, and people switch off. No matter how important your message is, it won’t be heard. And you may be taking up the time or phone line for more critical stuff.

There are some clear rules that can help keep your communication and minds on the mission upon execution –

Work with hard data, not assumptions. When task saturation is hitting you, it’s amazing how an opinion or assumption can morph into a ‘fact’ on which other people’s decisions are based. ‘How long have we got?’ can have only two answers: a number, or, ‘I will find out.’ If someone then wants your opinion, they’ll ask.

Your own jargon is OK. What is convenient shorthand within the team may well be jargon outside it, but the team should still use it. Pilots use terms like ‘inbound’ to mean ‘I’m On my way, on time, with no issues’, or ‘tumbleweed’ to mean ‘I have absolutely no situational awareness, and something bad could happen any time soon’, or ‘ballistic’ to mean ‘I am out of control and something bad will happen any time soon—stay away!’ That assumes, of course, that everyone knows what it means: it is part of the team’s language, part of its standards. Technical terms weren’t made up to be vague or confuse people. They are created to describe a specific thing in context, more efficiently than before.

Cut the chatter. Fighter pilots support each other by saying only what they have to say, no more, and then get off the radio. That keeps ideas clear and lines free. In business and at home, in most situations, that may come across as abrupt. But remember we’re talking about communication within a team that is focussing on a mission.

Decide on simple patterns for both one-way and two-way communication. For example, in two-way communication, agree on how to check you’ve made contact, that the other person is listening, and that they have heard you. Pilots aren’t shy in asking for a repeat back to make sure the word has got through: not the whole sentence, but a core word, phrase, or paraphrase. Similarly, agree on a simple structure for one-way communication. Set your own rules, whatever they are, and stick to them!

Shed Extra Tasks

It has always taken self-discipline to stay focused through our daily cacophony of personal and work plans, meetings, calls, and emails. That’s even harder now that we have a smartphone in our pocket 24/7 with its world of alerts, distraction, and temptation. So it’s become ever more critical to be able to cut through that task list and shed whatever you don’t really have to do, now.

Most time-management approaches follow similar themes (and Flex is no exception). The real difference with Flex is that you have wings, there to help keep you focused and shed tasks. If you need to, work with your wingman to problem solve how to shed tasks, and how to tap into other resources.

Each day or more often as needed, sift out what you have to do, and what you can shed! This will help you and your team stay focused on execution. Here is the way we prioritize things:

- Must do. Things that the law, your boss, your standards, or an emergency require you to do. You may not like them, you may rather do other things, but there’s no avoiding these! So best do or delegate them as quickly and as clearly as possible.

- Should do. Your core job. The missions you’re on, that take planning and diligence, and that your performance will be judged on—by you, your family, your boss, or your partners. Plan your days and weeks around these!

- Nice to do. These would definitely be worthwhile in the perfect world, but not at the expense of your core job. Things that contribute to the plans of others, to your learning, to your relationships. Do them by all means, but in gaps that emerge in your core program. The ‘nice to do’s can be a real trap

Sifting through and identifying the must do, should do and nice to do tasks, will help you and your team stay on track and achieve deep-performance results! Shed the unnecessary tasks and prioritise the tasks that will take you the furthest!

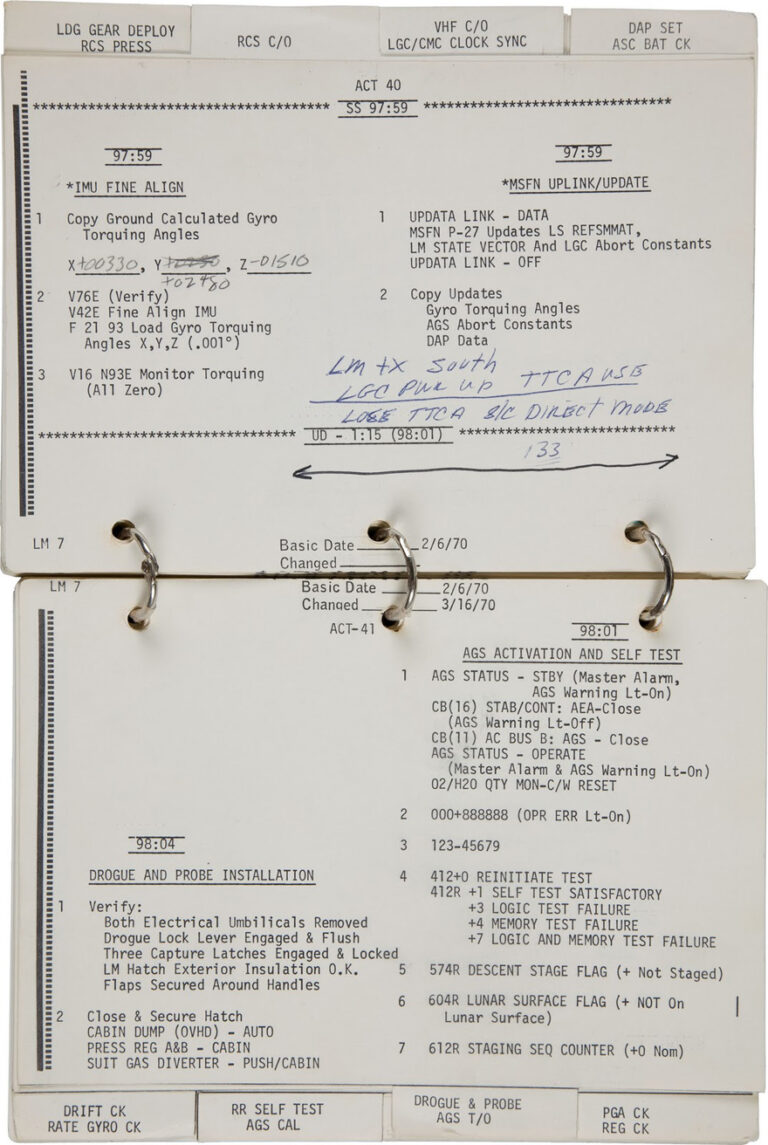

Checklists

Of all the things Afterburner teaches, two things stand out as commonplace in the air force, and rare as hen’s teeth in our personal and business lives: the debrief and the checklist.

Using a checklist means we’re getting ready for the execution of the plan. Working through a pre-flight checklist calms our nerves and puts us on the same frequency as our crew, our team, and our commander. Picking up an emergency checklist gives us time to think and respond. We know from our checklist that all the basics are in order so that our minds can drill down to the complexities of our mission and the creativity we’ll need to solve its problems.

Rules for all checklists

There are two critical rules for a checklist: keep it simple, and use it! The best way to ensure a checklist is simple and used is for the people who use it to be the ones who write it.

Trigger points that clearly determine when they are used.

One page. These are memory joggers, not phone books.

Nine steps or less, including cross-checks. Your team through their standard operating procedures will know what, if anything, makes those possible. There’s no need for ‘breathing steps’, as in ‘Remember to breathe’, that state the obvious.

Clear, concise language. Really push the meaning-to-ink ratio. If you don’t need a word, cut it. If it’s not clear to the operator what it means, replace it.

No distractions. Only what has meaning, no more! Basic fonts, no borders, no decorations, no emojis, no arrows to large words saying ‘This is important. Please read’, no such large words.

Test with other operators. Not only the team that developed the checklist but others. They’re the ones who will use them, and who will know if they’ll work.

Keep with the operation. If it’s a checkout checklist, keep it at the checkout. When it’s a pipe-testing checklist, keep it with the pipe. Maybe it’s a perforation gun checklist, keep it with the gun.

Read them aloud. The checklists are designed for an operator and wingman, whatever the task. Steps, cross-checks, and confirmations are always verbal, and if possible also visual.

We don’t like checklists. They can be painstaking. They’re not much fun. But we don’t think the issue here is laziness. There’s something deeper, more visceral going on. It somehow feels beneath us to use a checklist, an embarrassment. It runs counter to deeply held beliefs about how the truly great among us—those we aspire to be—handle situations of high stakes and complexity. The truly great are daring. They improvise. They do not have protocols and checklists. Maybe our idea of heroism needs updating.

Upon execution of your plan, it is essential that you keep your team to the plan. Understand what it looks like to lose focus, ensure you are identifying and supporting those that show the signs of shut down, flitterers, compartmentalizers and channellers. Use your wingman and use your checklists. Everything you have planned and evaluated has lead to this moment of execution, make it worth it!

No Comments